The propensity to pursue executive coaching: variables of self-efficacy and transformational leadership CEOWORLD Magazine

www.ceoworld.biz

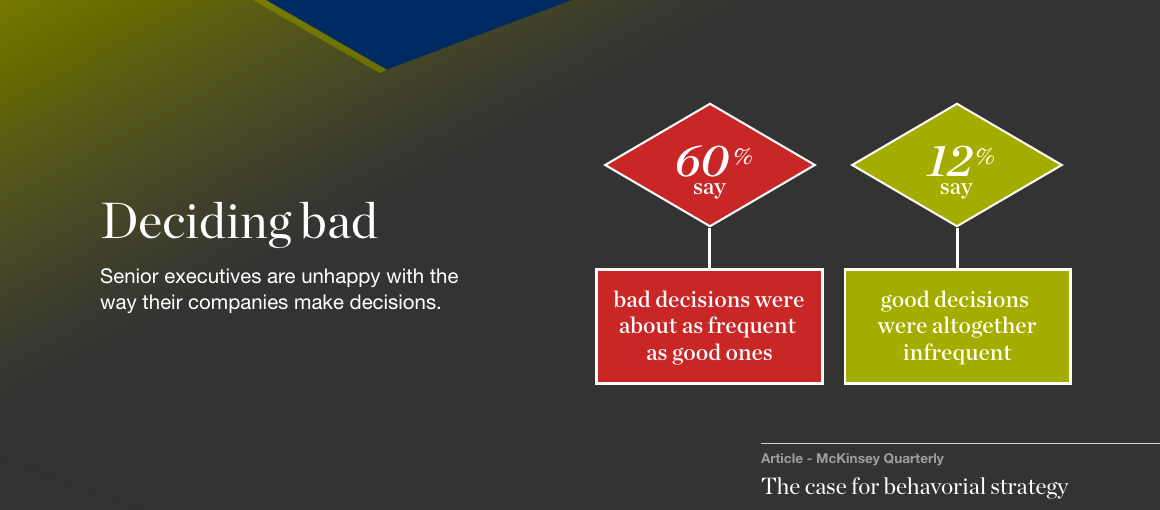

Two dominate variables, which has been linked to successful, sustainable, and innovative businesses is transformational leadership and leadership self-efficacy. However, nearly 60% of companies face leadership talent shortages (Crainer, 2011). Leadership coaching is a strategy to address the deficit of effective leaders (Gregory, Beck, & Carr, 2011; Hannafey & Vitulano, 2013), and leaders who seek coaching indicate improved self-efficacy and transformational leadership (Abrell, Rowold, Weibler, & Moenninghoff, 2011; Enescu & Popescue, 2012; Moen & Allgood, 2009; Mukherjee, 2012; Shanker, Bhanugopan, & Fish, 2012). According to the research literature and theorists, leadership coaching provides a new path for learning and self-awareness to an individual’s growth and development (Kay, 2013; Moen & Federici, 2012).

Unfortunately, a paucity of information exists about leaders who take responsibility for their own development, and McCall (2010) posited no substitutes exist for teaching evolving leaders how to take charge of their own advancement. Therefore, the objective of this research study was to (a) enrich the substantive theory building and empirical research on self-efficacy and transformational leadership by (b) assessing the leaders’ self-efficacy and transformational leadership, and(c) to ascertain if a relationship exists between these variables and the propensity to pursue executive coaching.

Theoretical Framework

Coaching continues to grow faster than research and Gregory et al. recommended an integration of theory and practical application of organizing frameworks. Control Theory (CT) posited humans take an active role or responsibility toward one’s behavior, where CT attempts to control the state of some variable, often the pursuit of accomplishing a task by controlling their behavior (Gregory et al., 2011).

Literature Review

Executive Coaching

In a comprehensive literature review by Kampa-Kokesch and Anderson (2001), the history of executive coaching is noted as barely traceable and a hard date for the commencement of executive coaching does not appear to exist. The word coach emerged in the 1500s into the English language to describe a particular horse drawn carriage. The origin of the verbto coach refers to a highly regarded person getting from where he or she was to where they wanted to go (Witherspoon & White, 1996). Over the centuries, the term moved through several avenues from sports coaching to academic coaching and to the evolution of executive coaching (Stern, 2004).

Predominately, western societies implement executive coaching. The United Kingdom reports 70% of companies use coaching, where 44% of employees report using coaching (Sergers, Vloeberghs, Henderickx, & Inceoglu, 2011), and 93% of companies in the United States (Jowett, Kanakoglou, & Passmore, 2012). The Coaching International Federation (CIF) reported an increase in membership from 1,500 in 1999 to 10,000 members in 2006 across 80 different countries (Jowett et al., 2012). Van Genderen (2014) asserted executive coaching is the fastest growing profession for the development of corporate success.

According to the CIF, coaching offers the definition as an ongoing professional relationship that helps people produce extraordinary results in their lives, careers, businesses, or organizations. Through the process of coaching, clients deepen their learning, improve their performance, and enhance their quality of life. (Brown & Rusnak, 2010, p. 15)

Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1986), a social cognitive theorist, first introduced the concept of self-efficacy. Social cognitive theory includes grounding in the conceptual understanding that human beings are vigorously committing to their development and actions (Bandura, 1986). Bandura (1997) postulated self-efficacy refers to a judgment of one’s own ability to perform a specific task within a specific domain. Thus, self-efficacy is the aspect of self, which refers to how sure (or how confident), the individual is that he or she can successfully perform requisite tasks in specific situations, given one’s unique, and specific capabilities. (p. 4)

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is a leadership style, which incorporates relationships and the dynamic interplay between the followers and the leader of a group. Transformational leadership inspires followers to be the best they can be, to accomplish their goals, and values what followers need and want. By focusing on the follower’s values and aligning those values with an organization’s value this outcome may further the mission of an organization (Givens, 2008).

Research Design

A quantitative study with a descriptive correlational design and linear regression analysis was used for this study with established self-efficacy and leadership instruments, which contain quantitative data to assess if a relationship exists between the variables. Applying a correlational design approach suits the needs of this study because the purpose is to examine if significant relationships exist between three sets of identified variables.

Population and Sample

The target population for this research study was executives in leadership positions (CEOs, COOs, VPs, CFOs, and executive management), which was accessed through SurveyMonkey®’s database. To avoid social and research exclusion, this study did not exclude gender or industry, but was limited to the United State. The study used a purposive sampling of executives. A standard email notification was used to notify respondents, that he or she had a new survey to take and the invite was a random group selected through an algorithm process. SurveyMonkey®’s solicited 186 responses with 110 of those responses being fully completed.

Instrumentation / Measures

The instruments used in this research study were selected because of their established reliability and validity measurements. The new general self-efficacy scale (NGSES) and the multifactor leadership questionnaire (MLQ) are established instruments (Bass & Avolio, 1997; Chen, Gully, & Eden, 2001). Participants received a survey, which incorporated the assessments NGSES and MLQ, to include a follow-up Likert-type scale question to ask how he or she self-rated their self-efficacy and transformational leadership (low, neutral or high), and then how likely he or she was to pursue executive coaching (Strongly disagree-Will not pursue executive coaching, Disagree – Might consider pursuing executive coaching within the next 3 months, Neutral, Agree, will definitely pursue executive coaching within the next 3 months, Strongly agree – will pursue executive coaching immediately).

Data Analysis

This quantitative correlational study used SigmaXL to run the descriptive statistics, correlations, and linear regression analysis. Minitab software was utilized to run the Cronbach alpha scores for the reliability and normality testing to reduce the risk of Type I and Type II errors of the instruments for this research project.

Results

Demographics

Male 56.76% self-reported as male (N = 63)

Female: 43.24% respondents self-reported as female (N = 48)

Ages: Position

18-30 – 22.52% (N=25) CEOs – 47.7% (N = 53)

31-40 – 33.3% (N=37) COOs – 15.3% (N=17)

41-50 -19.8% (N=22) VP – 7.2% (N=8)

51-60 – 21.6%) (N=24) CFOs -7.2% (N=8)

61-70 – 2.7% (N=3) Executive Management – 22.% (N=25)

Number of Employees

>100 – 46.85% (N = 52)

101 – 1,000 – 30.63% (N=34)

1,001 – 10,000 – 19.82% (N=22)

10,001< 2.7% (N=3)

RESULTS

Research Question 1: Does a relationship exist between self-efficacy and transformational leadership? The Pearson correlation is .691 with p < 0.000 therefore the null hypotheses was rejected and the alternative hypothesis was accepted demonstrating a significant relationship between transformational leadership and self-efficacy. These findings support Mesterova, Prochazka, and Vaculik (2014), which stated the two variables are positively paired, contribute to each other, and contribute significantly to effective leadership.

Research Question 2: To what extent does self-efficacy predict the propensity to pursue coaching?

The Pearson correlation is .167 with p < 0.08 therefore the null hypotheses must be retained and the alternative hypothesis rejected demonstrating no significant relationship between self-efficacy and the propensity to pursue executive coaching.

This was a surprising result to this researcher. A possible explanation for this finding is the purposive sampling of just high-level executives and their self-efficacy was assessed. The composite variable for actual self-efficacy was 4.5 (on a scale of 1-5) indicating a high-level of self-efficacy as self-reported by the respondents. The non-significant relationship between self-efficacy and executive coaching may indicate high-level executives feel quite confident, secure in their abilities, and do not feel the need to pursue coaching to enhance or develop their already existing level of self-efficacy. Additionally, the results of this research underpin Nease et al.’s (1999) research study where participants with robust self-efficacy would exhibit decreases in feedback acceptance.

Research Question 3: To what extent does transformational leadership predict the propensity to pursue coaching?

The Pearson correlation is .362 with p < 0.0001, therefore the null hypotheses was rejected and the alternative hypothesis accepted demonstrating a positive relationship between transformational leadership and the propensity to pursue executive coaching. The overall composite combined variable score for transformational leadership was high; therefore, transformational leaders may always feel a need to improve their abilities, promoting relationships, and enhancing their followers’ abilities despite their high scores. Transformational leadership, in definition, is a continuous growth path and one actually never arrives at full transformational leadership. Therefore, the results of this study support the characteristic domains of transformational leadership by demonstrating a desire to pursue executive coaching for continued growth.

Research Question 4: What is the relationship between self-efficacy, transformational leadership, and the proclivity to pursue executive coaching?

A linear regression model was calculated to predict likeliness to pursue coaching based on transformational leadership and self-efficacy. A significant regression equations was found (F = 11.8488, p < 0.000), with an R-square adjusted of 0.0905. The alternative hypothesis was supported indicating a small, only 10%, but significant likelihood when combining transformational leadership and self-efficacy, that an individual will be inclined to pursue executive coaching. Additionally, this result indicates transformational leadership may be a possible moderator on the variable self-efficacy, as self-efficacy as a standalone variable will not propel an individual to pursue executive coaching.

Limitations, Assumptions, and Future Research

A limitation to this current research study was the limitation of SurveyMonkey® to give the respondents in real-time their results of their assessed transformational leadership characteristics and scores of self-efficacy. This known variable may or may not have a different correlational relationship on the propensity to pursue executive coaching. Understanding the demographic variables of education, experience, or length in the executives’ current position may also help to elucidate the non-significant relationship between self-efficacy and executive coaching. Additionally, the industry of executive coaching is an established international industry and this research study was isolated to the United States. Replicating this same study in other geographic international locations may yield different results as well as for global companies or organizations in other countries.

Conclusion

First, to the industry of executive coaching when soliciting possible clients, transformational leadership is a construct, which leaders may be willing to explore, enhance, and continuously develop. Additionally, combining the assessments of transformational leadership and self-efficacy may influence a leader to pursue executive coaching. Furthermore, organizations, HR departments, and Board of Directors can administer the MLQ (5x) separately or combined with the NGSES and may see a willingness for the leader to pursue coaching to develop and enhance these skills on a deeper level. Leaders do appear to want to take charge of their own development and will pursue executive coaching if given the opportunity to assess their transformational leadership and self-efficacy.

REFERENCES

Abrell, C., Rowold, J., Weibler, J., & Moenninghoff, M. (2011). Evaluation of a long

term transformational leadership development program. Journal of Research Personnel, 25(3), 205-224. doi:10.1688/1862-0000

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. New Jersey, NY: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: NY, Freeman.

Brown, M., & Rusnak, C. (2010). The power of coaching. Public Manager, 39(4), 15-17.

Coaching International Federation. (2012). Retrieved from

Crainer, S. (2011). Leadership special report. Business Strategy Review, 22(2), 17-22. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8616.2011.00745.x

Enescu, C., & Popescu D. (2012). Executive coaching – instrument for implementing organizational change. Review of International Comparative Management, 13(3), 378-386.

Givens, R. (2008). Transformational leadership: The impact on organizational and personal outcome. Emerging Leadership Journeys, 1(1), 4-24. Retrieved from http://www.regent.edu/acad/global/publications/elj/issue1/ELJ_V1Is1_Givens.pdf

Gregory, J., Beck, J. W., & Carr, A. E. (2011). Goals, feedback, and self-regulation: Control theory as a natural framework for executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice & Research, 63(1), 26-38. doi:10.1037/a0023398

Hannafey, F., & Vitulano, L. (2013). Ethics and executive coaching: An agency theory approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 115, 599-603. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1442

Jowett, S., Kanakoglou, K., & Passmore, J. (2012). The application of the 3+1Cs relationship model in executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 64(3), 183-197. doi:10.1037/a0030316

Kampa-Kokesch, S., & Anderson, M. Z. (2001). Executive coaching: A comprehensivereview of the literature. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 53(4), 205. doi:10.1037/1061-4087.53.4.205

Kay, D. (2013). Language and behavior profile as a method to be used in a coaching

process. Poznan University of Economics Review, 13(3), 107-129.

McCall, M. W. (2010). Recasting leadership development. Industrial and OrganizationalPsychology, 3, 3-19. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2009.01189.xMesterova, J., Prochazka, J., & Vaculik, M. (2014) Relationship between self-efficacy,transformational leadership and leader effectiveness. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 3(2), 109-122. doi:10.12720/joams.3.2.109-122

Moen, F., & Allgood, E. (2009). Coaching and the effect on self-efficacy. Organization Development Journal, 27(4), 69-82.

Moen, F., & Federici, R. A. (2012). Perceived leadership self-efficacy and coachcompetence: Assessing a coaching-based leadership self-efficacy scale. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 10(2), 1-16. doi:10.5539/jel.v1n2p1

Mukherjee, S. (2012). Does coaching transform coaches? A case study of internal coaching. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 10(2), 76-87.

Nease, A. A., Mudgett, B. O., & Quiñones, M. A. (1999). Relationships among feedback sign, self-efficacy, and acceptance of performance feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 806-814. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.5.806

Segers, J., Vloeberghs, D., Henderickx, E., & Inceoglu, I. (2011). Structuring andunderstanding the coaching industry: The coaching cube. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(2), 204-221. doi:10.5465/amle.2011.62798930

Shanker, R., Bhanugopan, R., & Fish, A. (2012). Changing organizational climate for innovation through leadership: An exploratory review and research agenda. Review of Management Innovation & Creativity, 5(14), 105-118.

Stern, L. R. (2004). Executive coaching: A working definition. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 56(3), 154-162. doi:10.1037/1065-9293.56.3.154

Van Genderen, E. (2014). Strategic coaching’ and consulting: More similar than meetsthe eye. Middle East Journal of Business, 9(1), 3-8. doi:10.5742/mejb.2014.91368

Witherspoon, R., & White, R. P. (1996). Executive coaching: A continuum of roles. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 48(2), 124-133. doi:10.1037/1061-4087.48.2.124

++++++

By Dr. Shauna Rossington, DBA, LMFT.

0 Comments

2 + 7 =

RECOMMENDED ARTICLES

Executive coaching is back in fashion Economic growth in the UK has led to a resurgence in businesses u